It was a Sunday in late October my first year of teaching, and I was crying again. I was staring at a seemingly unending pile of grading and thinking about the 150 angst-ridden teenagers that would enter my classroom the next day. Other demands of my job were also rattling around in my head. The school initiatives, the newspaper article about the inadequate teaching at my failing school, my relationships with colleagues, paperwork for my students with education plans, parent phone calls I needed to make, evidence I needed to submit to yet another confusing online system as part of my evaluation—the list goes on and on. I felt like I was drowning.

The next morning, after a few fitful hours of sleep and three different alarms to get me out of bed by 5:00 a.m., I barely survived first period. A student who was in a fight with his dad expressed his feelings by throwing a stool across the classroom. Someone put a bar of soap (that I had bought for my students with my personal money) into my fish tank. I was overwhelmed and I felt like I was utterly incapable of success in my job. It was not that I was not trying, it was not that I was not passionate about the success of my students, and it was not that I was incapable of completing any one portion of my job. It just felt like there was too much to do and, as a result, I felt like I was not doing anything well. I walked into my principal’s office and announced that I was quitting. He barely looked up at me from behind his computer and simply responded with, “No, you’re not quitting. Now go back to class. Your class is about to start and I don’t have time to deal with this today. We are short on subs.”

He was right. I was not ready to give up on teaching yet. I had intentionally sought out a career where I would be consistently intellectually challenged and where I would feel like I was positively impacting my community. Now, six years into my career, I know that teaching is that career for me. But there are still days when the challenges feel too emotionally overwhelming.

As much as I wish there was a silver bullet to increase teacher sustainability, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions in education. Instead, teachers need to take the lead in exploring small interventions that can collectively increase the sustainability of teaching.

I am not alone in feeling overwhelmed by the realities of my profession. Both anecdotal stories from teachers across the country and quantitative statistics indicate that teaching often feels unsustainable. Although statistics vary, it is estimated that 9.5% of teachers leave the classroom within their first year of teaching and 40-50% of teachers leave the classroom within their first five years of teaching. Turnover in teaching is about 4% higher than in other professions (Riggs, 2013). Attrition rates of first-year teachers have even increased by about one third in the past two decades (Ingersoll & Smith, 2003; Ingersoll & Perda, 2010). Teacher turnover disproportionately impacts schools in high-minority and high-poverty communities (Boyd et al., 2005).

All of this supports addressing ideas of teacher sustainability as a worthy pursuit. To me, teacher sustainability means balancing the inherent challenges of teaching so that I am able to maintain my passion and interact with my work at a healthy, emotionally-satisfying level.

As much as I wish there was a silver bullet to increase teacher sustainability, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions in education. Instead, teachers need to take the lead in exploring small interventions that can collectively increase the sustainability of teaching. Over the course of the last year, I engaged in strengths-based observations of several of my colleagues. I found that these observations increased the morale of those teachers being observed, increased the morale of a teacher I completed the observations with, and increased my own morale. These improvements in morale contributed to feelings of emotional satisfaction and made teaching feel slightly more sustainable.

Threats to Morale

In order to explore what makes teaching feel sustainable, morale must also be investigated, as both are intimately intertwined with emotional wellbeing. Autonomy, sense of belonging, success, and celebration of accomplishments all contribute to morale. While there are patterns across departments, across schools, and across the country about threats to teacher morale, specific threats to morale are context-dependent. Last year was my first year as chair of the science department in my school. This leadership role compelled me to evaluate threats to morale at the department level.

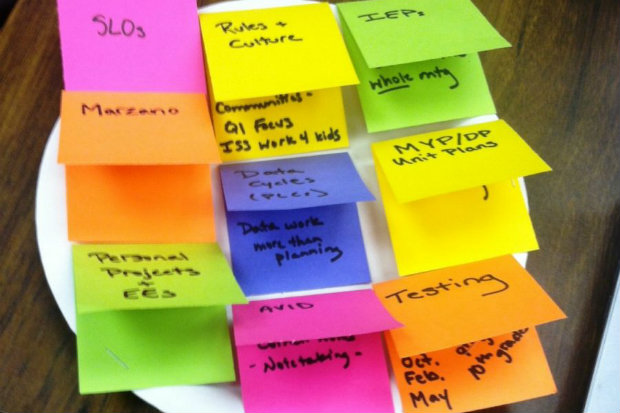

Figure 1: A representative depiction of demands on teacher time. Photo by Cacia Steensen.

To represent the demands on teacher time, I took a paper plate and stapled little colorful pieces of paper to the plate. On each piece of paper I wrote a single focus for the year. I meant for this plate to be a creative way to communicate with my department about the many things “on our plate” this year. The plate became a tangible way to discuss threats to morale throughout the year. Each thing on the plate, taken in isolation, is something that could be good for student learning. However, the plate as a whole was so full that each component lost its power. Plus, teachers had little power in choosing what was on the plate, and this lack of autonomy added to overwhelming feelings of discouragement. Morale in my department was crushed by heavy demands on teacher time, coupled with a feeling that teachers’ strengths went unnoticed.

I initiated a discussion during one lunch with the science department about morale. Several patterns emerged. For example, several teachers expressed not feeling recognized in the school for their positive contributions, as administrators in our building do not always know what is occurring in classrooms. The only time that teachers are observed by administration for extended periods of time in my school is during formal observations, which normally occur just once per year. Although administrators also complete informal observations for shorter periods of time, no science teachers had received any non-evaluative feedback from administration on their teaching. As a result, teachers felt that their successes in the classroom were going unnoticed. This feeling of being undervalued was made much worse by the incredible number of demands on teacher time.

Impacting the number of demands on teacher time felt beyond my control, so I instead tried to address the feeling of being undervalued by completing strengths-based observations of my department colleagues.

Strengths-Based Observations

While the many demands on our time impede much collaboration in our teaching, my department is rooted in trust. All 10 members of the department eat lunch together daily, and there are a lot of traditions in place that contribute to social connections between teachers. Therefore, all teachers within my department readily opened their classrooms to allow me to complete observations. A colleague and I observed another science teacher’s classroom for an entire period about once a month during our planning period. While this partner was not able to attend every observation with me, I was able to observe nearly all of my colleagues within the science department throughout the course of the year.

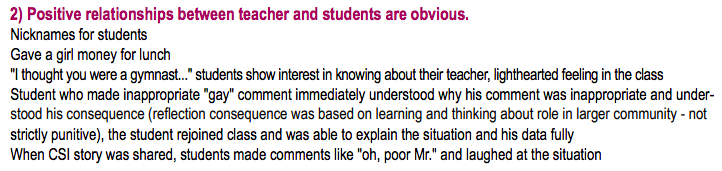

A Google Doc was used to organize each strengths-based observation around the guiding question, “What strengths are evident in ___’s classroom today?” During the observations, we created categories on the spot to capture each strength that was observed and then wrote down specific evidence to support that strength. We kept the categories organic and intentionally avoided using only the language present in the formal observation rubric. For example, in one classroom it was obvious that there were positive relationships between the teacher and his students.

Figure 2: Notes from strengths-based observation

At the end of the observation, we shared our notes with the teacher who was being observed. Working in a school that has been labeled by the state as “priority-improvement” led me to begin the early observations with the expectation that I would be challenged to identify strengths. However, I was consistently surprised at how easy it was to identify strengths within each classroom. Some teachers initiated a dialogue with me later about the observation and some did not, but all teachers expressed gratitude for the experience.

The Outcomes

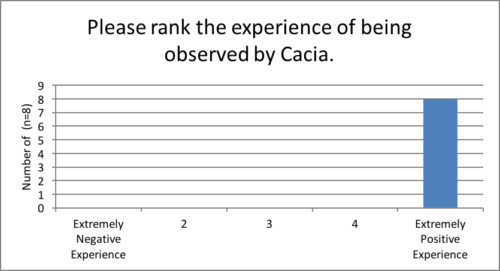

Completing strengths-based observations had positive impacts on the morale of the teachers being observed. Following the observation, the observed teacher was asked to respond to a short survey. Eight teachers responded to the survey. One survey question asked the teacher to rank the experience of being observed. All respondents (n=8) ranked the experience as being “extremely positive.” Teachers were also asked, “Did the feedback from the observations have any impact on your morale? Why or why not?” Every respondent indicated that the feedback had a positive impact on their morale. Two major patterns emerged as to why. First, several teachers wrote that getting the feedback made them more aware of what was going well in their classrooms. This increased confidence, made teachers feel more valued for their positive contributions, and increased morale. Second, three teachers wrote that the experience of being observed by colleague(s) from the department enhanced their relationships within the department. One teacher wrote, “I feel closer to my colleagues because we can feed off of those new perspectives.” This increased sense of professional belongingness had a positive impact on morale.

Figure 3: Survey data from peer observations

Additionally, completing strengths-based observations had positive impacts on the morale of the teacher that completed the observations with me. This colleague was new to my school last year and was only a second-year teacher. I audio-recorded a few of our conversations from the second semester so that I could reflect on patterns in her thinking. Throughout the year she had several points where she expressed feeling totally overwhelmed and discouraged. Although it was her second year teaching, she reflected that it felt more challenging than her first year teaching because she felt like there were far too many different initiatives, that it was challenging to learn how to navigate all of the systems in place within our district, and that there was an overarching sense of low morale in our school. She was not able to attend all of the observations, but she was positive about the observations she was able to complete. After the first observation, she commented on an engagement strategy that used stamps. She said, “It was helpful to observe our colleague as it made me reflect on my own practice. The stamp idea that he uses, I am using it now in my honors classes and they are super into it. They all want to stamp each other. The whole point of observing is to get ideas and reflect on how we can improve ourselves so focusing on strengths is good. Nitpicking my colleagues would not be fun for me so I don’t want to do it—I want to focus on strengths.” In fact, after each observation that she attended, she had at least one new idea for how to improve her own practice. Towards the end of the year she said, “Observing was so much more helpful than the professional development that our school does. I was able to actually see what the strategies look like in classrooms. Also, because it is from our colleagues, I know that it will work with my kids. Some of the stuff the school does feels like it doesn’t apply to me.” Overall, completing the strengths-based observations positively impacted my colleague, her sense of efficacy in her own class, and her connections within the department.

Completing the strengths-based observations had positive impacts on my own morale as well. I left every observation feeling inspired by my colleagues. While it would have been easy to identify places for improvement in the instruction I observed, focusing on only strengths was far more powerful for me. I do not think focusing on strengths made me any less aware of weakness but, instead, made the observations more emotionally supportive for me. After the first observation, for example, I was impressed by the relationships between the teacher and his students. After the observation, he seemed apologetic that his students were not more focused on the lesson at hand. From my position as an observer, however, his students were engaged the majority of the time and their strong relationship with their teacher helped support their learning. This difference between how the teacher viewed his lesson and how I viewed his lesson put my own teaching in perspective. This was helpful in framing my own classroom successes, realizing I am often hypercritical of myself.

While I already felt like the social relationships I had with my colleagues were positive, completing the observations made me feel like I had a better sense of their actual teaching skills. As I became more acutely aware of their professional talents, I was filled with pride at being a member of such a capable team. This pride led me to value my identity as a member of the science department even more than I had prior to the observations.

The observations also increased my feeling of autonomy and expanded my locus of control about my teaching. Because I completed the observations independently, without administration or district oversight and management, I felt I was in control of my own development and of the relationships within my department. This autonomy was emotionally satisfying. Though there were few tangible strategies I changed in my instruction as a result of the strengths-based observations of my colleagues, completing the observations had a significant positive impact on my morale. In turn, increasing my morale enhanced feelings of sustainability in teaching. Because the largest threat to feeling sustainable is time, it seems almost counterintuitive that the observations were a positive force as they took time away from my planning. But, the increase in my morale and the subsequent increase in feelings of sustainability were greater than the planning time that was lost.

Implications for Sustainable Teaching

During my first year of teaching, I was on the brink of quitting nearly daily. While I now have fewer days when being a teacher feels impossible, I still feel that actions need to be taken to make teaching feel more sustainable, so that my fellow teachers and I can continue in this career, which we so value. Many of the challenges that make teaching feel unsustainable are beyond our control, but there are some concrete actions that we can take to improve feelings of sustainability and address morale. Participating in strengths-based observations is one such action.

The strengths-based observations increased the morale of those teachers being observed, as well as the morale of the teacher who completed the observations with me and my own morale. More seemed possible with renewed energy, joy, and hope to balance some of the challenges of teaching that can feel crushing. Completing strengths-based observations is, by no means, a comprehensive solution to address teacher sustainability. More time, more money, and more respect from society would help, for example. However, teacher-led, strengths-based observations are one tool that allowed me to feel like I can continue to pursue my passions in this profession. I no longer am regularly on the brink of quitting and intend to continue to build my own sustainability with strengths-based observations as one tool.

Cacia Steensen is a Knowles Senior Fellow who teaches biology and IB Biology in an urban school in Colorado; she recently became the department chair for her school’s science department. Cacia can be contacted at cacia.steensen@knowlesteachers.org.