Hierarchy of Teacher Needs

A Model For Understanding Teacher Needs

Society places a long list of responsibilities and expectations on teachers. The Pew Research Center (2024) found that 84% of K-12 teachers in public schools said they do not have enough time during work hours to accomplish all of their tasks. This leads to teachers working, on average, more than 54 hours a week, well beyond their usual contracted time (Najarro, 2022). Much of their contractual hours are spent instructing and supervising students, grading, and giving feedback, along with the myriad logistical aspects of being a teacher. As a result, teachers often want more time to plan, prepare, and work with colleagues (Najarro, 2022).

Teachers need time, space, and mental energy to engage in routines that will move our practice forward.

In order to improve our practice, teachers need time, space, and mental energy to engage in routines that will move our practice forward. A sentiment shared by many teachers is that it is hard to try to revamp curriculum, participate in inquiry, or share knowledge with others when you are just trying to survive on a day-to-day basis.

New teachers are often the most susceptible to this roadblock. When teaching something for the first time, it is difficult just to complete logistical tasks like making tomorrow’s copies. Finding additional time and energy to improve their practice on top of everything else can feel impossible. This lack of time also leads to newer teachers being overlooked as sources of knowledge for teacher improvement.

Even veteran teachers struggle to find a balance. Take, for example, back-to-school professional development. As we start the year, our internal clocks are still adjusting to the school schedule, we are thinking about how to get supplies set up for the first day of school, and we are starting to plan the first weeks or months of class. All of these aspects of teaching pull our attention away from professional development (PD) that introduces big new practices that, let’s be honest, are often forgotten about by October, making that PD feel irrelevant to the needs we have right now.

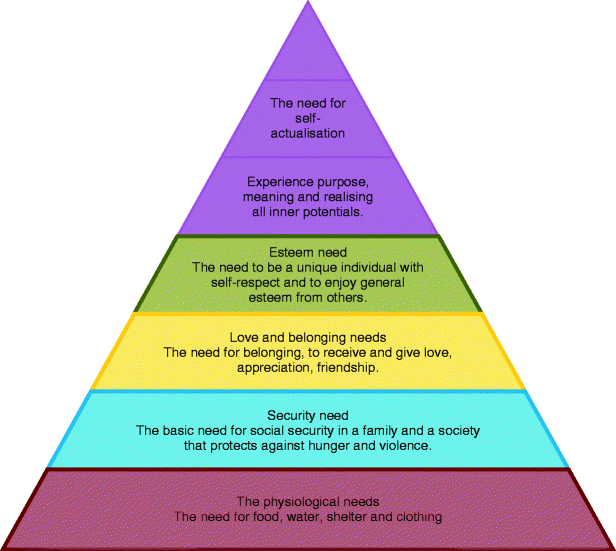

Based on this thinking, we started to compare these roadblocks for professional inquiry to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as shown in Figure 1 (Block, 2011). In this framework, people have physiological, psychological, and self-fulfillment needs. We see Maslow’s hierarchy at work every day with our students. 75% of educators work with students who come to school hungry, and when they get there, most say that their hunger makes school difficult (No Kid Hungry, 2023). We understand that students who show up unfed, experience housing insecurity, or face abuse or neglect at home do not have the capacity to try that challenging physics problem.

Figure 1

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (Block, 2011)

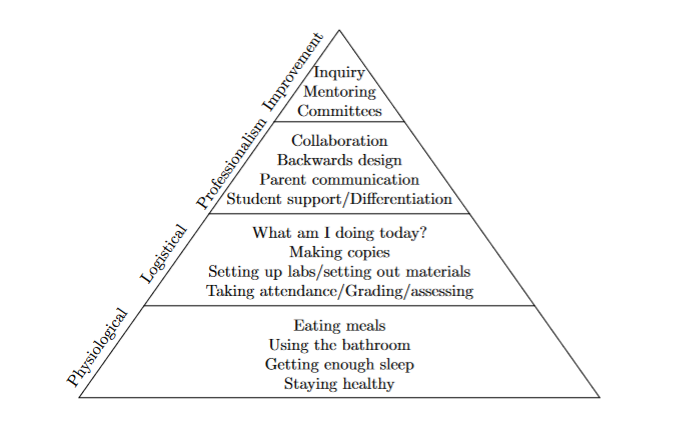

Like anyone else, teachers must have their needs, as defined by Maslow, met. However, in our professional practice, there seems to be an additional, separate hierarchy of needs, which we have deemed the “Teacher’s Hierarchy of Needs” (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Teacher’s Hierarchy of Needs

The Tiers of the Hierarchy of Teacher Needs

At the very bottom of this hierarchy are the basic “Physiological” needs of teachers. Just like our students, we cannot be expected to do our best work on an empty stomach, with a full bladder, when we’re overstressed, or as an insomniac. However, the structure of our job often gets in the way of some of those needs—students who need help limit our time to eat lunch, a classroom full of students delays us from going to the bathroom when we need to, piles of papers to be graded prevent us from getting enough sleep. Not to mention illness: we work in a germ-filled environment and often try to muscle through a mild cold rather than write plans for a substitute teacher, leaving us with reduced physical and mental capacity. When these basic physiological needs are not met, we might barely have the energy or stamina to move up the hierarchy; planning more than a day in advance becomes nearly impossible.

The next level of the hierarchy represents the bare minimum a teacher needs to do in order to perform their job, which we have termed the “Logistical” level. Every day, no matter what, a teacher needs to have a plan for the day; they need to take attendance, grade, and make copies; they need to set out the appropriate materials for that day’s lesson. Even when a teacher is sick, the logistical needs must be met—we need to write sub plans, submit our absence, and post materials to Google Classroom. No contractual day in a teacher’s working year goes by without requiring them to complete some or all of the logistical tasks in this level.

When a teacher can get their head above the deluge of logistical tasks enough to breathe for a second, there are the tasks that are still expected of teachers, but that offer more flexibility, which we term the “Professionalism” needs. These include contacting parents, differentiating instruction, collaborating with colleagues, and long-term planning. All of these important tasks are expected of teachers, but typically are not considered urgent enough to be slotted into our daily schedule. When we are having an especially hard week, we might be able to get by without checking all of these boxes, but on the whole of the school year, they are still expected of us.

Finally, with whatever time a teacher has left, they might be able to satisfy their “Improvement” needs. After a teacher has met the bottom three tiers of needs, they can then start to think about how to improve their practice on a broader scale. When we can take a step back from the deluge of tasks, we can look at our practice through inquiry, mentor newer teachers, and participate in school-wide committees. Teacher inquiry requires time to repeatedly collect and analyze data and develop avenues for improvement. Mentoring asks teachers to devote their time to helping new teachers, and school-wide committees call for teachers to step out of their own practice to help make improvements to the school system. These activities help us improve both our practice and the school community. However, to expect teachers to meet these needs without first ensuring that their physiological, logistical, and professionalism needs are met is to ask something almost superhuman.

In order to reach those professionalism and improvement stages, I needed time and support, which I received from my students, colleagues, and administration.

Justin’s Experience

In my sixth year of teaching I was starting at a new school. Many of the base-level needs that I regularly met at my previous school were now challenges as I acclimated to a new space. The bathrooms weren’t quite as accessible between classes, the bell schedule was different, and lunch fell at a strangely brunch-y time. Additionally, I had a new student information software (SIS) to use for grades and attendance, another physics teacher to collaborate with for the first time, and a 15-month-old whose post-move preferred wake up time was 5:00 a.m. All of these changes thoroughly disrupted my ability to engage with any sort of meaningful practitioner inquiry or even the back-to-school PD. Through the first two months of school, I was working hard to simply meet my physiological and logistical needs as a teacher.

As the year progressed, I began to settle into my school more and more. Occasionally I would still try to use a password from my previous school or forget that tomorrow is a RAM day, not a Blue day, or “oh, there’s a faculty meeting today after school—it was on that one calendar, didn’t you see it?” But, in general I was meeting my physiological needs—there was a secret faculty bathroom just around the corner from my classroom that I hadn’t noticed and my toddler rediscovered how to sleep until 6:45 a.m.—and logistical needs—my physics colleague shared copies and labs, and I became proficient with the new SIS. By mid-March, I was able to engage with my inquiry group in Knowles, participate as a member of my school’s professional development committee, and write a grant proposal.

In order to reach those professionalism and improvement stages, I needed time and support, which I received from my students, colleagues, and administration. I had a mentor, the other physics teacher, who helped me adjust and was a great source of FAQ-style logistical support; there were monthly new-teacher meetings with the other new-to-the-school teachers and administration so we could develop community and share our struggles; and every two weeks, we had 45 minutes of Professional Learning Community (PLC) time where the physics teacher and I could co-plan lessons, labs, and assessments—or just run and make some copies.

Matthew’s Experience

In my third year of teaching, I was given the role of PLC facilitator. Inspired by my experience in Knowles, I wanted my PLC to engage in inquiry work to collectively improve our practice. The only problem: this was Fall 2020 and we were adjusting to the new normal during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We were worried about getting COVID (physiological needs), we were teaching using virtual and hybrid instruction for the first time (logistical needs), we were trying to reach students who were not sitting in front of us (professional needs)—our lower-level teacher needs were not met. While we had more time to meet than ever before (my school instituted “asynchronous Wednesdays” with no students), we were so focused on our physiological, logistical, and professional needs that improving our practice felt irrelevant at that time.

I came to my PLC so excited to use our extra meeting time to revamp our curriculum and our grading. My colleagues were initially on board with this, but each meeting devolved into griping about the way the school handled the pandemic (making us feel unsafe or unsupported), trying to figure out how to have class discussions with some participants online and some in person, or devising ways to provide better supports for students. By the time we scratched the surface on these topics, there was no time or energy left to engage in improving our teaching practices.

But, there is a bright side: the next year, when students were back in person and things were (kind of) back to normal, our experienced PLC was able to then engage in this work. We leaned on our experience of in-person teaching to make the logistical challenges surmountable, we knew how to effectively support and differentiate for students who were sitting in front of us, and remaining health concerns were less pressing. That year, we critically looked for the meaningful parts of our curriculum, making many cuts to provide time for more interactive instruction and student practice. We also developed a set of standards and laid the groundwork to switch to standards-based grading the following year. When our physiological, logistical, and professional demands were met, we were able to share in the work of improving our classes.

Recommendations

So, what can be done to help teachers meet their lower-level needs so that we can have meaningful, inquiry-driven professional growth?

Our recommendations for district and state policymakers are:

Ensure that teachers are not struggling to meet their physiological needs.

- Pay teachers a living wage, and provide good health insurance, sick leave, and parental leave. Reduce the burden and the stigma around taking a sick day. Provide teachers with resources and supports to encourage work-life balance and create an expectation that work stays at work. Create school-wide structures for student support that do not rely on individual teachers giving up their lunch or planning periods.

Provide time for teachers to engage with improvement work when their other needs are fully addressed.

- This means more than a quick morning meeting when they are preoccupied with what they are teaching in 45 minutes. Plan for more time than expected— this allows teachers to check off their logistical and professional needs, and still attend to their improvement needs.

Our recommendations for school administration/leadership are:

Provide stability.

- Logistical needs will continue to arise if teachers are assigned new courses every year. Professional needs will interfere with improvement if grading policies change midway through a semester. Assigning teachers the same courses with relatively stable school-wide policies reduces teachers’ logistical needs each successive year, and thus allows them more bandwidth to improve their practice.

Provide structures for teachers that open up time for them to focus on their improvement needs.

- Pay attention to timing of professional development. Inquiry work may be more valuable to teachers before a break when they are not focused on what they are teaching the next day.

- Encourage teachers to explore professional development opportunities where they can disengage from their context, removing the constant reminders of copies to be made, tests to grade, and parents to contact.

Our recommendations for teachers are:

Establish work-life boundaries.

- Designate specific times for grading, planning, and other work-related tasks, ensuring you protect time for personal life and relaxation. Avoid taking work home unless absolutely necessary, and use your planning periods effectively to reduce after-hours work.

Develop efficient systems for daily tasks.

- Use technology (grading software, online classrooms) or other resources to automate or semi-automate tasks like grading and attendance. For example, use numbered cell-phone pouches to get a quick view of attendance or have students log into Apple Classroom with their laptops.

- Batch similar tasks (e.g., grading, lesson planning) to streamline your workload and minimize task-switching. Instead of grading and planning everyday during a prep period, grade one day and plan another. Getting “in the zone” allows you to be more efficient and effective.

Focus collaboration time with colleagues.

- When opportunities arise for collaboration, enter with clear expectations and goals for those meetings. If there is a task or stated goal to be met, the meetings can be efficient and meaningful.

Start small with your own professional development.

- Growing and improving as a teacher doesn’t happen overnight, so don’t overburden yourself with a massive PD project or graduate classes if you don’t feel supported. Instead, find 15-30 minutes a week to dedicate to learning about your practice—this could be analyzing student data with a colleague, creating a reflection journal focusing on what you did in class that week, or looking for longitudinal trends in your assessment data. Those 15-30 minutes a week add up to hours of meaningful inquiry across your school year.

Obviously, many of these recommendations require large, organizational change. But not all do. With this teacher needs framework, we invite district and school leaders to consider the reasons teachers struggle to improve their practice. We hope that teachers take solace in this framework by identifying why it feels hard to meaningfully engage in improvement practices. Our recommendations offer ideas for school leaders and teachers to work together to ensure teachers’ needs are met so they can grow and schools can advance.

Citation

Dudak, M., & Ragland, J.. (2025). Hierarchy of teacher needs. Kaleidoscope: Educator Voices and Perspectives, 12(1), https://knowlesteachers.org/resource/hierarchy-of-teacher-needs.