The Work is Theirs: Honoring Student Thinking Through Task Design

As teachers, we often devote much of our energy to planning lessons that feel smooth, organized, and engaging for students. We aim for clarity, structure, and a sense of momentum in the classroom. But, too often, these well-designed and orchestrated lessons ask students to follow instructions rather than construct, create, and develop ideas. The disconnect between what a lesson looks like on the surface and the kind of thinking it demands is one of the most challenging, yet critical, tensions we face in our practice.

This tension was highlighted for me one day as a student teacher. I was expecting my advisor to observe me, and I had poured myself into lesson planning for that day. My slides were packed with animations and images, my lab was “hands-on,” and I crafted detailed instructions with key questions at the end to check for understanding. I truly believed I was doing everything right. I was supporting the students I cared so deeply about.

“This was going to be the best lesson yet!,” I thought to myself. That day, students were going to extract DNA from strawberries- the scientist and teacher in me was buzzing with anticipation. Students filed in, did the warm-up, and took Cornell notes during my animated DNA presentation. I moved through the rows, checking in, answering questions, and keeping everyone on track. Then came the lab: materials ready, instructions followed, students busy. I was everywhere at once. I was monitoring, prompting, and making sure students had everything they needed to complete the task.

At the end of class, I made sure to wrap up everything neatly. I revisited key points and answered every lingering question so no one would be left confused. I was sure they were learning. After all, everything looked like it was going exactly as I had planned. I got through the whole lesson and the lab. I was even looking forward to my debrief with my advisor.

When we sat down to debrief, I was feeling pretty proud. I thought everything had gone smoothly. But then my advisor asked, “What do you think your students learned today?”

I blinked. “Well… they learned about DNA. They even got to see it with their own eyes.” I said it more professionally than that, but inside, I was confused. Weren’t you there? Didn’t you see how engaged they were?

Then came the next question: “What did they do?”

I paused. “They took notes… did the lab…followed all the steps perfectly…”

And then they asked, “Who was doing the real work of learning?”

That question hit hard. I started replaying the lesson in my mind. If I were being honest, I had done most of the thinking. I guided every step, gave explanations, answered every question, and made sure there was no confusion. I was the one doing the heavy lifting. I was the one making meaning.

My students? They were following directions, staying on task, and doing what I asked. They were compliant, but not really engaged in sensemaking. In that moment, I could see the cracks in my lesson design and my instruction. That debrief forced me to take a hard look at the kinds of lessons I was designing and, most importantly, who they were designed for.

After that conversation with my advisor, I couldn’t stop thinking about how much I had been doing for my students, how much I had protected them from struggle. The truth is, I saw struggle as something to avoid. I thought my job was to make learning smooth and frustration-free. If students were confused or stuck, I jumped in right away to help.

My thinking shifted. I started to see that by shielding students from struggle, I was also shielding them from learning. Struggle isn’t a sign that something’s gone wrong. Struggle can be productive and a necessary part of making sense of complex ideas. I had been stepping in with the best of intentions, but in doing so, I was taking away my students’ chances to wrestle, to wonder, to try and fail and try again. I was the one doing the learning, while they were just doing the following. That realization pushed me to rethink how I designed lessons and to ask a new question: How can I create space for my students to do the hard, messy, meaningful work of learning?

Once I understood that struggle was a productive component of learning, I knew I needed to make some changes. But I also knew I couldn’t just throw students into the deep end and hope they’d figure it out. I had to be intentional. I needed support. I needed tools and strategies that would help me design tasks where students could truly engage in sensemaking. Tasks where they are doing the heavy lifting, but with the right kind of support. Over time, I found a few approaches and tools that helped me strike that balance.

This was a pivotal learning moment for me as a teacher and one I like to share as a teacher educator by having the teachers I support ask the important question:

What types of thinking do my tasks demand of my students?

The lessons I had so carefully planned as a beginning teacher asked students to do different kinds of things. Some, like my polished DNA PowerPoint and the strawberry extraction lab, asked students to follow procedures, recall facts, and stay on track. They looked good on paper and felt productive in the moment, but they didn’t really invite students to make sense of ideas for themselves.

What I was really after was something deeper. I wanted to create space for students to wrestle with concepts, to make connections, and to build understanding for themselves. The quote from 5 Practices for Orchestrating Productive Mathematics Discussions resonated with me:

“Different tasks provide different opportunities for student learning. Tasks that ask students to perform a memorized procedure in a routine manner lead to one type of opportunity for student thinking; tasks that demand engagement with concepts and that stimulate students to make connections lead to a different set of opportunities for student thinking.” (5P-M, p. 15)

That quote from 5 Practices helped me name what I had been circling around: it wasn’t just about how a lesson looked—it was about the kind of thinking it asked of students.

This is the framing I leaned on:

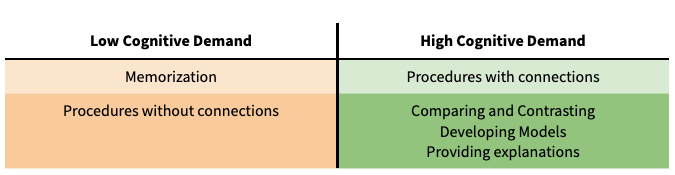

Tasks that ask students to perform a memorized procedure—those are low cognitive demand. Tasks that ask students to engage with concepts, to make connections, to do the heavy lifting of sensemaking—those are high cognitive demand. And those are the kinds of tasks I was after. Tasks that create space for real thinking. Tasks that invite students to take risks, get stuck, make meaning, and grow because of it.

Tekkumru-Kisa, M., Stein, M., and Schunn, C. (2015)

Realizing this wasn’t just about doing more. It was about doing things differently. I knew I needed a way to reflect on and revise my lessons. I didn’t have to toss everything out and start over. Sometimes, the shift came from tweaking just one aspect of a task: the way I introduced it, the kinds of questions I asked, or the space I left for students to think before stepping in.

One tool that really helped me was the Task Analysis Guide, adapted from Tekkumru-Kisa, M., Stein, M., and Schunn, C. (2015). A framework for analyzing cognitive demand and content-practices integration: Task analysis guide in science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(5), 659-685.

It gave me a structure for thinking through how a task functioned in my classroom, what kind of thinking it asked of students, and whether it created opportunities for productive struggle. This tool didn’t give me a script or a list of “good” or “bad” tasks. Instead, it helped me ask better questions about the tasks I was already using:

- What are students being asked to do here?

- What is my role?

- Where is there space for sensemaking, grappling, and building ideas?

Using the Task Analysis Guide helped me look at my lessons with fresh eyes. It allowed me to keep the parts that were working and revise the ones that weren’t, creating space for deeper thinking. And slowly, task by task, I began to shift my practice.

Looking back, that strawberry DNA lab didn’t fail because students were off-task or disengaged. It failed because I hadn’t created space for them to truly think. That lesson, and the questions my advisor asked, set me on a path I’m still on today: learning how to design for sensemaking, not just compliance.

This work isn’t about perfection. It’s about paying attention to what we ask of our students, to know when and how to step in, and whether the task itself makes room for authentic learning. The shift toward high cognitive demand doesn’t require a complete overhaul of your curriculum. Sometimes, it’s just a thoughtful tweak, a better question, or a bit more space for students to puzzle through something on their own.

Tools like the Task Analysis Guide have helped me keep my focus where it belongs: on student thinking. And while I’m still learning, I now know what I’m after: less polish, more grappling. Fewer tidy answers, more honest sensemaking. Because that’s where the learning lives.

If you’ve ever found yourself doing all the heavy lifting while your students quietly follow along, you’re not alone. The good news is, change doesn’t have to start with a brand-new curriculum—it can start with a question, a small revision, or a fresh look at a familiar task. I’d love to hear what this brings up for you. What kinds of thinking are your tasks asking students to do? What’s one small shift you’re curious to try?

Works Cited

Smith, M. S., & Stein, M. K. (2011). 5 Practices for Orchestrating Productive Mathematics Discussions. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Tekkumru-Kisa, M., Stein, M., and Schunn, C. (2015). A framework for analyzing cognitive demand and content-practices integration: Task analysis guide in science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(5), 659-685

M. K., & Smith, M. S. (1998). Mathematical tasks as a framework for reflection: From research to practice. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 3 (4), 268-275.